The “Oppressed” Muslim Woman

We have a new damsel in distress in the media: the Muslim woman. You know the image I’m talking about – a woman peering at you through black fabric, her eyes begging for help, her hijab representing the binding shackles of Islam. Maybe instead of just one woman there is a group, a wave of black all blending together in one homogenous mass. There might even be an adventurous white woman thrown into the mix, ready to free Muslim women from their oppression!

Muslim women are consistently represented poorly throughout Western media, which overemphasizes their appearance, portrays them as weak and oppressed, and strips away their individual identities, transforming them into a homogenous group. Only 24% of the people in the news are female, but the Muslim women in particular have it even worse. A 2007 study in the UK found that 91% of articles in national newspapers about Muslims  were negative, which, when combined with the underrepresentation of women in the media, means that when Muslim women do sporadically appear it is rarely in a good light. The poor portrayal of Muslim women skyrocketed during the invasion of Afghanistan as a side effect of the propaganda used to rally support for the military advance. In 2001, Laura Bush stated the war on terror was “a fight for the rights and dignity of women.” When the headscarf was banned in France in 2004, people like Margaret De Cuyper of the Netherlands enthusiastically supported the move, since “women have lived for too long with clothes and standards decided for them by men; this is a victory,” despite the fact that those banning the hijab are themselves primarily men dictating what women can and cannot wear. Islam is not a monolithically oppressive religion, and a hijab does not mean weak, it does not mean silenced, and it most certainly does not mean oppressed.

were negative, which, when combined with the underrepresentation of women in the media, means that when Muslim women do sporadically appear it is rarely in a good light. The poor portrayal of Muslim women skyrocketed during the invasion of Afghanistan as a side effect of the propaganda used to rally support for the military advance. In 2001, Laura Bush stated the war on terror was “a fight for the rights and dignity of women.” When the headscarf was banned in France in 2004, people like Margaret De Cuyper of the Netherlands enthusiastically supported the move, since “women have lived for too long with clothes and standards decided for them by men; this is a victory,” despite the fact that those banning the hijab are themselves primarily men dictating what women can and cannot wear. Islam is not a monolithically oppressive religion, and a hijab does not mean weak, it does not mean silenced, and it most certainly does not mean oppressed.

In response to this overwhelming rhetoric of the “oppressed” Muslim woman, artists are investigating what it really means to be a modern Muslim woman. These artists are going against mainstream portrayals to showcase strong, intelligent, and independent women who have stories beyond the stereotypes that accompany what they choose to wear on their heads.

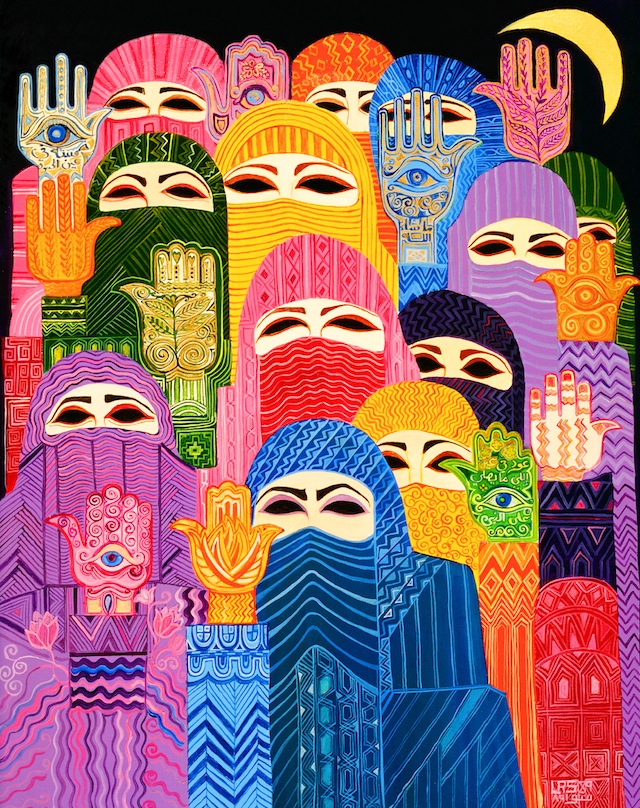

One such artist is Hassan Hajjaj, whose work has been showcased in art museums and galleries around the world. Hajjaj was born in Marrakesh, but moved to London where he worked as a DJ, a stylist, and a designer before focusing on his art and splitting his time between the two cities. His exhibition, “Kesh Angels,” documents the biker culture of the young women of Marrakesh in a way that directly challenges the assumption of the mutual exclusivity of being independent, modern, and confident while also being Muslim. His portraits feature Marakkeshi women wearing abstract, colorful veils and djellabah (traditional Moroccan dress) while posing on their motorbikes,all against a Moroccan backdrop. The traditional dress combined with Moroccan biker culture and the emblems of famous western brands, like Nike and Gucci, serve as a stark contrast to the dark, depressing images of Muslim women that are more prevalent in the media. These women are educated, run their own businesses, and traverse Marrakesh on motor bikes like total badasses – definitely not the kind of women in need of saving.

The niche devoted to showcasing art that challenges stereotypes of Muslim women is growing, and there are an increasing number of impressive collections dedicated to demonstrating the development. The International Museum of Women has an online exhibition, Muslima, which is dedicated to showcasing women’s art and voices. It features a colorful array of work spanning the globe, but unites its collections under the theme of exploring what it means to be a modern Muslim woman. There are paintings, photosets, videos and interviews covering everything from the challenging of stereotypes to coming-of-age stories.

photosets, videos and interviews covering everything from the challenging of stereotypes to coming-of-age stories.

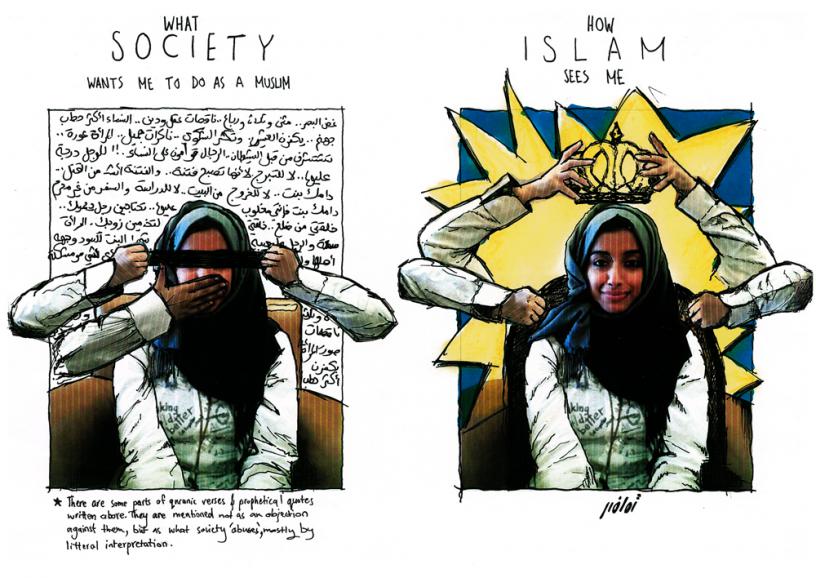

Muslima features artists like Tamadher al Fahal from Bahrain, who creates ‘zines’ to display her frustrations surrounding the injustices and inequalities against women in the Arab world. Zines are small circulation, noncommercial publications, and Fahal’s “Diary of a Mad Arabian Woman” is devoted to looking at the contradictions and conflicts in the Middle East through the eyes of a young woman. She explores the difficulty of “being an independent individual with a successful career, yet maintaining the principles of Islam,” as well as the “pressure of other cultures… that cast a general wrong impression… about Muslim women.”

She uses the dichotomy of what society wants her to do as a Muslim and how Islam itself sees her to both critique the society she lives in and challenge the negative perceptions of Islam around the world. She uses Quranic verses in the background of her portrait “not as an objection against them, but as what society ‘abuses,’ mostly by literal interpretation.” Bahrain certainly has its own societal issues regarding women’s rights – women only received full suffrage in 2002 – but she manages to present her criticism in such a way that makes a distinction between the oppression within her own society and the supposed oppression of Islam. The Muslim faith is not what contributes to her issues within society; rather, her issues stem from people’s abuse of Islam to further their own political aims.

There are oppressed Muslim women throughout the world (just like there are oppressed women everywhere, regardless of religion or ethnicity), but the association between the hijab and oppression is yet another example of the tendency to reduce other cultures to one symbol and use it for one’s own agenda, whether it is to support military advances or the assimilation of marginalized minorities or general xenophobia. It is crucial to take a more critical look at the media portrayals of Muslim women, and not just because women like Fahal and those pictured in Hajjaj’s work deserve our respect. In a country with rampant Islamaphobia, the constant bombardment of the negative images of Muslims has very real consequences, and it is crucial for the media to change the discourse surrounding Islam.

So you tell me – do these women look oppressed to you?

5 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

I loved this article it really summed up how I felt about people thinking I’m oppressed for wearing a hijab. I am currently doing a research paper in school about muslim females representation in the media focusing on the fashion industry and i would love to hear your views or opinions on this.

[…] profit from perpetuating the stereotype of the weak Muslim woman ― a tactic also used at times by Western media and American […]

[…] profit from perpetuating the stereotype of the weak Muslim woman ― a tactic also used at times by Western media and American […]

[…] profit from perpetuating the stereotype of the weak Muslim woman ― a tactic also used at times by Western media and American […]

[…] from perpetuating the stereotype of the weak Muslim woman ― a tactic also used at times by Western media and American […]