Suburban Policy in City Life: The Far Reaching Consequences of Housing Discrimination

BY GRACE FEENSTRA

When considering pressing urban issues, it may seem counterintuitive to look at the suburbs as an important factor in urban policy. However, the explosion of the suburbs can provide important information about government policy relating to cities, and about systemic discrimination that lingers to this day.

The current tax code provides several incentives for homeownership. Residential construction and the costs associated with homebuilding are important components of the national economy, and the federal government attempts to stimulate this construction through tax credits for those who take out a mortgage to buy a home. These tax credits are not available to city dwellers who pay rent on an apartment. The government has taken significant steps to guarantee and insure loans made to those who want to own a home. In addition, highway infrastructure is highly prioritized, making the commute into the city quick and easy for those who wish to live elsewhere.

In order to build the large number of homes needed after World War II, the government turned to private builders. At the time, there were few large construction corporations, but the profit incentive led to a spike in large builders, who bought huge tracts of land and could construct a large number of homes inexpensively. These large companies also formed housing lobbies that went to Washington D.C. to ensure that the government preference for suburban living would continue. While not directly targeting urban living, these government policies have made it so that, over the last 50 years, homes in the suburbs have been financially appealing to large groups of Americans. Over the course of the last few decades, the combination of inexpensive housing and tax credits for home ownership – along with campaigns designed to portray the green, open living in the suburbs as a preferred alternative to crowded urban life – has resulted in the middle and upper class moving away from the city. Today’s cities have a smaller tax base and are less able to provide important services to their inhabitants.

Another important aspect about the trend towards suburban life is the way in which the move to the suburbs is polarized by race. Suburbs skew largely white across the nation, and this trend is particularly prominent in certain cities such as Milwaukee, known as one of the most segregated cities of America. The city of Milwaukee is over 40 percent African-American, but only 2 percent of people in the Milwaukee suburbs are African-American. Although scholars initially believed this could be due to the propensity of races to live together, research makes it clear that institutionalized racism plays a large role in this racial disparity, as minorities are often denied access to suburban living.

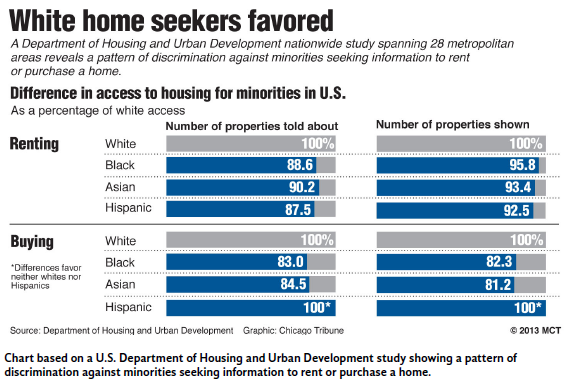

There are several stages during which discrimination plays a role in the housing process. According to Motley Fool Real Estate Trailblazers, local governments can write zoning codes that do not allow for multi-family homes or specify large minimum lot sizes; this excludes low-income families, often people of color, from many suburban areas. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) undertakes an extensive studies of real estate agent discrimination. The most recent study, in 2012, shows that minorities are less likely to be given information about available houses and are shown fewer units than whites. Agents also use language to steer white prospective buyers away from neighborhoods with large numbers of minority residents. This accentuates the segregation already prevalent in cities. Insurance companies and lending agencies have historically discriminated against minorities. The federal government itself once participated in these discriminatory trends, although in recent decades it has put measures in place to try to stop discrimination on the part of financial institutions.

There are several stages during which discrimination plays a role in the housing process. According to Motley Fool Real Estate Trailblazers, local governments can write zoning codes that do not allow for multi-family homes or specify large minimum lot sizes; this excludes low-income families, often people of color, from many suburban areas. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) undertakes an extensive studies of real estate agent discrimination. The most recent study, in 2012, shows that minorities are less likely to be given information about available houses and are shown fewer units than whites. Agents also use language to steer white prospective buyers away from neighborhoods with large numbers of minority residents. This accentuates the segregation already prevalent in cities. Insurance companies and lending agencies have historically discriminated against minorities. The federal government itself once participated in these discriminatory trends, although in recent decades it has put measures in place to try to stop discrimination on the part of financial institutions.

Despite stricter enforcement, studies still show that minorities face higher denial rates for financing than their white counterparts. Without available financing, suburban life becomes inaccessible. The multiplicity of agents in the private market who participate in the housing process means that there are plenty of opportunities for discrimination at each stage. Although reforms, such as the Community Reinvestment Act, make it more difficult for agents to discriminate, recent studies show that minorities who seek to buy a home in the suburbs are often not given the same information and assistance as their white counterparts.

Policymakers should not assume that all people have a desire to live in the suburbs – many may prefer staying in the city limits to moving farther away. The option of moving to the suburbs, however, is not available for many people due to discriminatory practices, and the financial incentives the suburbs provide then also become out of reach. Not all Americans wish to live in the suburbs, but this should be a choice by the individual, not a reality imposed due to discrimination in the process.

Residential segregation is important, not only because of tax incentives that those in the city do not receive, but also because of the far-reaching consequences of residential segregation. For most Americans, their home is their primary financial asset. The ability to pass on a home, or the value of a home, to future generations provides long-term wealth in a family. Those who are unable to get financing to own a home or who have houses in lower-valued neighborhoods have less generational wealth to hand down. Family wealth, not income, is a key factor in outcomes linked to health, educational attainment, crime, and other social statistics. Continuing to perpetuate wealth disparities between races will lead to many poor, often minority youth, who attend schools in cities with a shrinking tax base, and whose families do not have the wealth to send their children to better schools or provide them with the resources needed to succeed.

The foreclosures in the wake of the Great Recession, which disproportionately impacted minorities, have only broadened this gap. In 2009, white Americans, on average, had 20 times the wealth of African Americans, and 18 times the wealth of Hispanic Americans, according to a Pew Research Center study. These gaps have increased since 2005, and are the largest since the study began 25 years ago. The foreclosures in the recession have led to new forms of discrimination. Houses that have been foreclosed on in white neighborhoods tend to be maintained and kept in better condition by the bank than houses in predominantly minority neighborhoods. Ill-kept houses lower the house price and neighborhood appeal of surrounding homes, meaning that the wealth of those in surrounding homes decreases as well.

Life in the city is, in part, defined by life in the surrounding suburbs. Life in the suburbs is important, but a closer analysis of who can live in the suburbs and what that life affords someone shows that the suburban trend continues to polarize groups in America. Choosing to live in the suburbs is not, in and of itself, negative. The problem lies in the fact that suburban life is financially incentivized through various government programs, and that only certain people have access to that suburban life. Urban policymakers must consider how to attract people who might otherwise live in the suburbs back to the city (while not forcing out the residents already there) and national policymakers must consider how to be certain that discrimination in the housing process is eliminated. Where one lives is an essential part of quality of life, and therefore we must focus on what the growth of the suburbs means for us today.