The Power of Paper

I was recently going through various boxes, drawers, and bins around my house. Among the pictures of my three-year old self and old VHS tapes, I found one of the most powerful remnants of this millennium: the front page of The New York Times from September 12, 2001. I hadn’t known we still had that, and it took me more than a few minutes to fully reabsorb the banner headline and the pictures below.

Aside from the memories I have about that day twelve years ago, what else could have stirred such vivid feelings? Perhaps it was the physical paper in my hands. Having something that powerful in my hands, being able to manipulate it, move it closer, fold it, turn it, all allowed me to enhance my experience, and I fear that with the decline of print news, the same intimacy I have been fortunate enough to share with events both local and global will be harder, even impossible, to attain in the future.

Newspapers are woven into the fabric of American society. In any portrayal of the first forty-odd years of the twentieth century, one of the most common features is a young boy selling newspapers and yelling, “extra!” Perhaps the most iconic job for any child with a bike is a paper route. For many years, one of the hallmarks of big cities was a widely respected, well-read newspaper. I have even been instructed on the proper method of folding a paper for optimal convenience when on a subway. So what has happened to newspapers, that quintessentially American form of communicating information?

From before the assassination of Abraham Lincoln to the present day, readers of newspapers have been captivated by the banner headlines that proclaim, with the most emphatic of tones, that which is most recent and most important. I remember my dad teaching a younger me how to look at the front page of a newspaper and tell which stories were more important. I remember asking, with wonder, if he had ever seen a banner headline.

In a world where speed is the name of the game, a printed piece of paper that must be laid out, sent to the press, organized, wrapped up, and delivered takes a long time to get to its final destination. In its short existence, the Internet has done away with the delay between an event occurring and its being publicized. In addition, the number of sources from which one can get information has increased exponentially. Anyone with access to a computer or a smartphone can blog, tweet, or post anything they want to and have it instantly available to the entire connected world. Consider the Arab Spring; much of the initial information, as well as the organization of protests, was made public by average citizens, not seasoned reporters, and all these citizens needed was access to the Internet. Immediate, online news isn’t necessarily bad, but it doesn’t compare to news provided by a trained journalist.

As much as the global availability of information is a good thing, this glut of information also comes at the cost of quality and reflection. It is all too easy to push thoughtful debate to the sideline while under pressure to get the story out before the competition. In contrast, a story’s life in the realm of paper consists of editing, revising, more editing, and more revising. As a result of the high standards any well-respected publication holds itself to, nothing gets printed without passing through the strictest scrutiny.

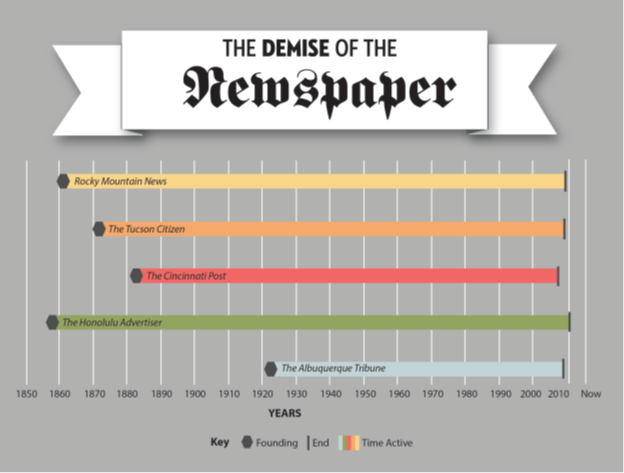

Paper media is certainly on the decline. Founded in March of 2007, NewspaperDeathWatch.com, a site that follows the declining newspaper industry, lists over ten American metropolitan newspapers that have folded over the last six years, as well as several others that have decreased the frequency of their publications. At the beginning of October they ran a small piece about how at the end of the year, Lloyd’s List, a publication dedicated to maritime shipping and the self-proclaimed world’s oldest daily newspaper, will cease producing its print edition and move entirely towards an online format.

This shift is representative of how newspaper companies are reacting to the changing news delivery environment. As people increasingly own tablets and other mobile devices with which they can easily access the internet, the papers that adapt to the digital age fastest and most fluidly will have the best chance of surviving and maintaining their influence. However, even the most well designed, user-friendly layout will never compare to the feeling of thin paper between fingers, the sound of crinkling while flipping from page to page, and the minimal loading time from article to article.