The Price of Skinny Jeans

BY MATTHEW HANKIN

Before last spring, few Americans had heard of Rana Plaza, an illegally constructed eight-story building in Savar, Bangladesh. On April 24th, 2013, the building, which contained textile factories that supplied skinny jeans and other garments to Walmart and other American and international brands, collapsed, killing over 1,100 workers and injuring approximately 2,500. Eight days after the industrial disaster, the worst in Bangladesh’s history, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina tried to push it out of the headlines, stating, “Accidents happen.” Finance Minister Abul Maal Abdul Muhith similarly dismissed the Rana Plaza building collapse as not “really serious,” claiming similar industrial accidents occur “everywhere.” The great tragedy of the Rana Plaza disaster, though, is that it was not an accident, but a catastrophe brought about by profit-driven disregard for the safety and well being of factory workers.

The day before the factory collapsed, workers noticed large cracks in the building that prompted engineers to advise complete evacuation. A private bank and shops on the first floor of the building closed and all workers were asked to leave. Despite never being cleared for safety, management ordered garment workers to return to the factory the next day or else forfeit a month’s salary and risk dismissal. Many workers, wholly dependent upon the job for their livelihood, felt they had no choice but to return to the building they knew to be unsafe. These work- ers’ fears were tragically confirmed the next day, when thousands became trapped beneath the building’s debris.

In Bangladesh, powerful industries exert tremendous influence over the policies that directly affect workers’ rights, and much of the political leadership have vested interests in promoting profit over safety. Around 50 percent of all members of parliament have some business connections to the garment industry, and nearly 10 percent of the country’s national legislators directly own garment factories. This creates incentives for policymakers to ignore the needs of workers in the interest of personal gains. Government inaction to improve worker safety is not merely oversight; it is the calculated attempt of politicians to increase their own income at the expense of workers, who are treated as inputs to production rather than as equal citizens. Workers’ lives are so devalued that, at the time of the accident, there were only 18 factory inspectors for the nearly 4 million people who are working in the textile industry. To this day, many families of the victims of Rana Plaza still await the promised $20,000 government compensation, unable to collect because nearly 300 bodies were buried without identification.

Although Bangladesh is more involved in the global economy than ever, workers have not seen any gains from this growth. International forces played a large part in the Rana Plaza disaster: with about 23 percent of the country’s exports going to the US and 60 percent going to Europe, foreign companies play a major role in shaping the conditions in Bangladesh. Foreign companies profit from the extremely low Bangladeshi minimum wage and the minimal amount spent on insuring worker safety, which has led to increased investment in Bangladesh. This investment has propelled the country to become the world’s second largest clothing exporter, behind China.

As news of these horrendous conditions spread after Rana Plaza, the United States reacted to the disaster at Rana Plaza with the largely symbolic, yet significant, move to revoke the tariff benefit for Bangladesh known as GSP (Generalized System of Preferences). The removal of GSP will cause a drop in exports of only about .8 percent, or $40,000,000, but sends a strong signal to the Bangladeshi government without necessarily reducing the employment opportunities that so many Bangladeshi’s desperately need.

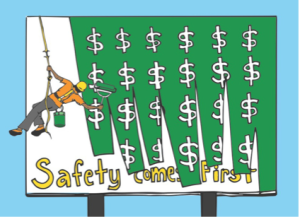

H&M, the largest purchaser of garments from Bangladesh, took a similar step forward when it partnered with other apparel companies and signed a legally binding agreement that forces companies to invest in fire-safety and building improvements in the factories they use in Bangladesh. Other companies, like Gap and Walmart, have not followed their good example. Instead Walmart and Gap opted to enter into a volunteer agreement that lacks transparency and enforceability called the “Bangledesh Worker Safety Initiative.” The initiative consists of general promises that cannot be legally enforced. If Walmart did not decide to enforce safety regulations on good faith before the collapse, why will it voluntarily decide to now?

As retailers on the whole still prefer working in Bangladesh rather than in higher-wage countries like Vietnam and Cambodia, questions revolving around worker rights will not go away any time soon. Real progress in improving safety conditions will only come after the hu- manity of workers is acknowledged. The first step in this process lies with consumers’ decisions to support companies that have made legally enforceable commitments to workplace safety in Bangladesh. In effect, these legal commitments are promises to view employees as people, ensuring they will be workers in factories, not bodies in rubble.

Matthew Hankin is a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences. He can be reached at mhankin@wustl.edu.