The Tenure Tradeoff

It’s Complicated

Universities are peculiar organizations. A student’s relationship to a university can take multiple forms; but fundamentally, we, as students, are its customers. On paper, we pay to prepare for the rest of our lives, but anyone who has had a work-study job or a research assistantship will tell you that students are also the university’s employees. Perhaps most importantly, the university and its students are expected to make each other look good. By going out and making an impact in the world, we give the university a good name: the same good name we use to further the reach of our impact. In short, it’s complicated. What, then, can students expect the university to consider when hiring professors for tenure or tenure-track positions?

Washington University is a research university. In order to get tenure, a professor must also be a high-quality researcher, which means different things in different fields. Usually, it means publishing journal articles and, ideally, books. In the natural sciences, a professor directs a lab and mentors graduate students. Teaching, while not wholly irrelevant, is arguably the least of the major criteria. In short, a research university cares more that a professor can further a body of knowledge than impart it. Professors that primarily teach are usually called lecturers and receive both less pay and job security.

The previous argument implies a trade-off between good teaching and good research abilities. Yet, professors can be both brilliant academics and good communicators in a classroom. (This writer has certainly had plenty of professors who are both.) However, the system as it is structured is not intentionally designed to train teachers. Doctoral candidates are expected to perform research for their entire program, usually around five years, while taking a certain credit requirement. Along the way, they act as teaching assistants for two or three courses. This is hardly adequate preparation for facing a lecture hall with eighty students. The way tenure is structured means that teaching—especially for undergraduate classes—is almost an afterthought.

This means that the good professors in the classroom are the ones who want to be good, or are naturally gifted. They do not have to be, nor are they trained to be.

Many students have expressed their dissatisfaction with this tenure process. Teaching, they argue, should be given more weight than it is now. After all, the returns of engaging, effective teaching are enormous. Not only are we more focused in a classroom, we learn more, and we may find what we love to do because of an inspiring professor. Moreover, tuition is not cheap, and for the amount one pays for a Washington University education, a student would be justified in asking for the best classroom experience on offer.

Why We Really Go To Washington University:

Economists, like Michael Spence in his seminal 1973 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, have extensively studied the impact of education on a person’s wage. The assumptions at play are that a liberal arts education is a good thing, but not as important as getting a good job. While it’s clear that a higher education level (up until a point) means a higher income, it’s not clear why. One theory frequently cited is that education imparts skill sets that workers use. Another is called signal theory, which argues that what we actually learn at college isn’t important: it’s important that we were at college, because it signals to an employer that we mean business. While both are no doubt feasible theories, the latter is more relevant to Washington University. The actual material that we learn isn’t too different from what a student at another university would learn. And the fact that we pay so much more is a function of the importance of name brand.

This is a generalization. The liberal arts education provided by Washington University may not be found elsewhere. However, getting a job often outweighs the liberal arts approach for most students. The basis for this is anecdotal, but the number of students who complain about the cluster system, and take easy classes to ‘get the requirement out of the way’ is suggestive.

Unfortunately, therefore, we overestimate the importance of professors; Washington University students are capable of succeeding in most courses without a brilliant instructor. A good textbook, help sessions, and practice are usually enough. We don’t primarily enroll in university to learn from a professor. Many of us are here to tell employers, graduate schools, and investors that we are worth hiring.

What Research Does

By hiring professors who are brilliant in their field and constantly publishing, the university furthers its name. When this happens, it attracts the best and brightest students, research funding, and more professors. The university grows in stature and size, and even helps to create a fertile environment for local job growth. This has been Washington University’s story; and in its eyes, its duty to its students has been fulfilled.

The ultimate question boils down to determining what a university’s obligation to its students is. Ideally, we would have the best minds and the most engaging professors. Unfortunately, that may be asking for too much; but between furthering the body of knowledge in academic disciplines and giving us its reputation, Washington University is doing plenty.

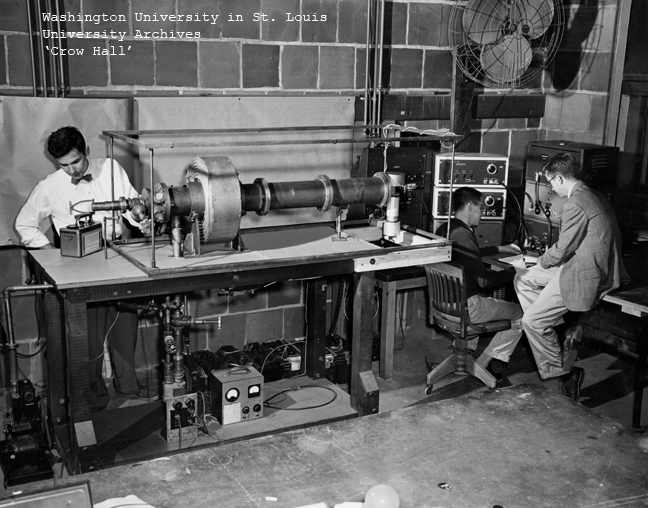

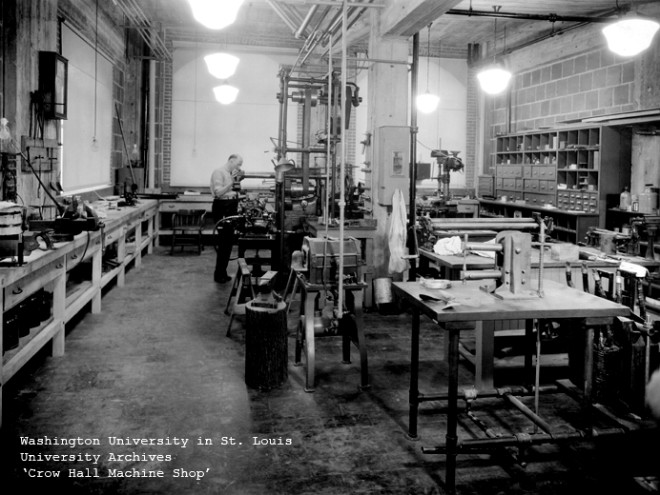

Without its emphasis on research, the university wouldn’t begin to approach its current endowment value of $5.35 billion. The university’s recent push towards the biomedical sciences has left students in other disciplines feeling a little hard done. While an underfunded department isn’t ideal, the departments that do well offer a compelling template. Until recently, the Biomedical Engineering department had two of the most cited chemists in the country. With an army of graduate students, and a publication or two every year, they convinced investors that money spent on their department was money well spent.

Arguably, Washington University needs to work just a little harder than most peer universities to attract the best talent. While St. Louis is a richly storied city, it sometimes struggles to retain researchers who would rather live in Chicago, New York, or in California’s Bay Area. To that end, nothing keeps the best minds like the promise of funding, and nothing procures funding like rewarding the best minds.

In the end, the winners are the students. Signaling aside, students have the opportunity to engage with the best in the business. Many students even perform research under their guidance. Even if none of this were the case, however, having a Washington University education on one’s resume counts for a lot more when the university consistently supports the world’s brightest academics.

Any further disagreement with the University’s way of appointing tenure boils down to disagreements over what the university’s obligation to its students is. Ideally, we would have the best minds and the most engaging professors in the classroom. In order to get that, however, American research universities teaching requirements need an overhaul. Unfortunately, this may be a pipe dream. Personally, I’ll take having a class with an academic celebrity as a pretty good consolation prize.